10 Favourite Self-Written Film Reviews of 2025

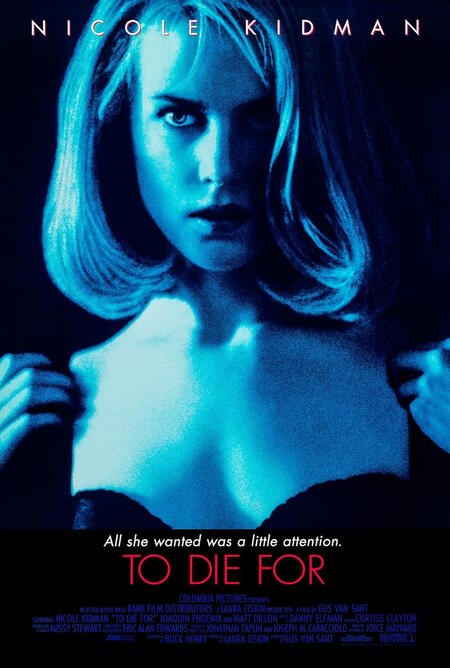

1. To Die For (1995) ★★★½

“You’re not anybody in America unless you’re on TV.”The elevation of artificiality in a manufactured society, made for TV. A special broadcast of American narcissism: The Suzanne Stone Story.True to her maiden name, Suzanne is inflexible and hard. A stop-at-nothing woman trying to ascend her no-steps journalism career ladder, her choice to use Stone instead of her husband's surname, Maretto, in the professional setting is self-centredness masked as (hypocritical) individualism as she exaggerates the importance of her position at a local network, working day in and out over a self-created project without care nor time for her over-doting husband (or anyone, really). This act of exaggeration fools us right from the start, giving the impression that Suzanne Stone is a well-established TV personality with her well-styled hair, well-made clothing, and well-trained smile. She dresses as if she's already made it. But she is merely a weather presenter in a small town. Immediately, we also learn she is suspected of her husband's murder, tuning us to the station of sumptuous satire and detestable deception.Instead of fucking her way to the top, Suzanne Stone fucks her way to manipulation. The notion of American success and identity she touts is as narrow and flat as the television screen she so wants to see herself on, constructed, taped, and transmitted to influence the viewers akin to the influence she wields on the teenagers she exploits. It is an imposition of power distinct in any display of suburban moral decay. Because Suzanne is the lowest in hierarchy at her drab workplace, with no other professionals to speak or hang out with, she finds/forces an audience in the aimless youth of the local high school, preying on their fantasies as much as she is preyed upon by her own fantasy of fame. She longs for popularity only to have infamy to her reputation. Her vision of goodness is also put-on: everyone will only do good if they are watched, mirroring her worldview of a televised morality. TV is also framed truth and reality. Suzanne embodies this as a mouthpiece of society’s obsession with appearances and celebrities. “She just looks clean," says Phoenix's teenage Jimmy, who she renames to James as a way to make him believe his worth, his appeal. Later on, she turns his fantasy into reality. Yet however real it is, the intentions around it are also framed, forged. Like Jimmy, his classmate Lydia also falls for the same trick, though circumstances somewhat amusingly turns around for her. In a certain degree, she attains what Suzanne cannot.Misleading narratives spooled with devious determination, “To Die For” is a farcical assemblage of TV programmes. From candid interviews to self-absorbed narrations with a white background insisting on integrity to late-night show with the parents to standard thriller, it hops from one channel to the next, then back again, making us piece together Suzanne Stone as Gus Van Sant intended: a relayed aggregation of her own words and words of people she knows, because, perhaps that is the closest we could get to the truth and see the lie. Today, we are overloaded with information presented at various angles, and images rendered by editing software (or worse, artificial intelligence). It is up to us to discern between fabrication and fact. The film provokes the same discussion. Media tools may be more advanced, more deceiving, but the purpose and agenda of those in power (i.e. those who have these tools) hardly change.“To Die For” is diabolically hilarious but struggles in maintaining the balance of its tone throughout. By the time it teases itself as a murder inquiry, it fortunately regains its footing, wickedly encasing the artificiality, the narcissism underneath a harsh winter. Partly, it is an ironic comeuppance of Suzanne Stone. It complements her skater sister-in-law’s one-word description of her. But there is somewhat a chilling air of doubt in this resolution. Subconsciously, we know the winter season will end. Snow will thaw. Ice will melt. In this land will appear some new age artificiality and narcissism. And as usual, everyone will watch.May be one of the funniest ending lines in a film ever. Gasped and guffawed.“It’s nice to live in a country where life, liberty… and all the rest of it still stand on something.”

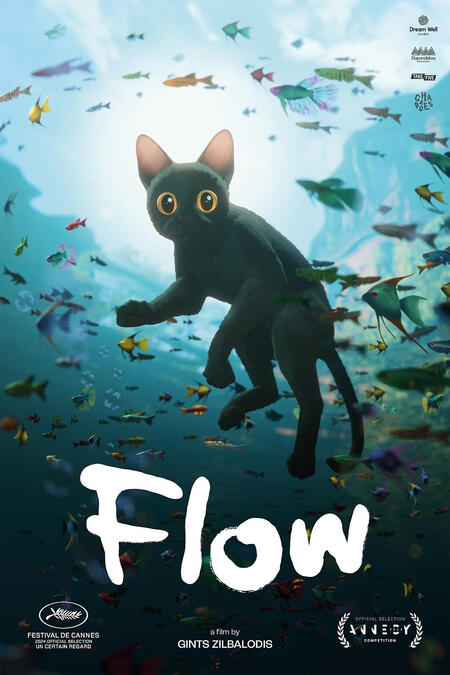

2. Flow (2024) ★★★★

The soil of the earth unpeopled vanishes in the deluge of near extinction. Along the engulfing apocalyptic waves of this now aqueous realm pulses the instinct for survival. Creatures solitary, creatures in packs and in pairs swim, wade, and search laboriously for some shore, some island, some patch of land away from the ripples of irreversible catastrophe, away from their homes and habitats entirely inundated. As the water level continues to rise, refuge is a sail on a boat, adrift across miles and miles of blue into the darkest turbulent blues, where different animals embark and alight, some wary, while others are friendly, one is frightened, another is occupied with their salvaged glinting possessions. Primal drives deflect the wordless anthropomorphisation of their sound and look, where each purr, bark, squawk, whine, tilt of the head, turn of the neck, and roll of the body translate into recognisable human expressions. Yet they’re more human than us in their hesitant teaming up in this modern fable of climate disaster, past their differences and past the hate and past the predation; for others this is temporary, for others this is permanent, out of necessity, out of sheer goodwill. The leviathan plunges deep far from its symbol, also affected by the human-wrecked tempers of the earth, breathing its seeming last amongst the emergence of new lands, the receding waters making way for craggy terrains. A meditative voyage across ethereal visuals on the ceaseless flow of life itself, up the swirling clouds of finality and into the terraces of continuance, its kiss of mortality a touch of solidarity, all the relics and the monuments, this Roman edifice, everything will eventually be swallowed, taken by time accelerated by our reckless mangling of this one world of ours, and we will be underpinned alone by our reflections of coexistence and community.

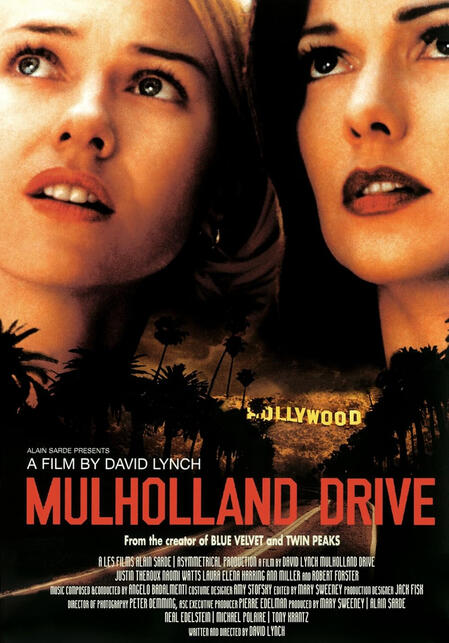

3. Mulholland Drive (2001) ★★★★★

What are dreams if not our subconscious desires and our deep-seated fears, if not the latent exercise of control the mind latches onto against an unpleasant reality uncontrolled, bending it hither and thither within the cosmos of intoxicating slumber? “Mulholland Drive” conceives such a realm. Out of its car crash of a Hollywood promise slithers a concussion of reverie. Its dreamer reweaves threads of rejected actualities into illusionary manifestations, where mere fleeting figures in real life occupy major roles (waitress Betty, the nameless actress at the party) in the fanciful reinvention. In these strangers belong lives unknown, which are easier to make up and fill out through the dreamer’s subconscious imaginative will. They offer a clean slate amidst a sullied existence; the failed ambitions reworked, the toyed affection repaired. Thematic elements converge largely as an exhibit of profound yearning. Frequently, it thrives in the fantasy, seesaws in the mystery between the blur of sleeping and waking. And through integrating, adopting, and assembling other selves under the same appearances, the yearning is sated. Or so it seems.In the grand scheme of things, “Mulholland Drive” is a love story bedecked with frills of neo-noir. The dreamer helping her Rita find herself is a construction of an elaborate cerebral maze in making Rita (Camilla Rhodes) return to her as she knows her, wants her. That the director Camilla Rhodes (Rita) gets on with is subjected to many kinds of losses is a way for the dreamer to regain herself, her love, her career, her life. She triumphs over him (and Camilla Rhodes) by having the semblance of directing this dream, directing Rita, while he faces many obstacles before he can direct his film. “It'll be just like in the movies. We'll pretend to be someone else,” Betty excitedly suggests. And so, in part, this is also Rita and Betty’s impassioned rehearsal before the perverted audition. Two of them alone in amnesiac desire before it is intruded by the tragedy of remembering. Because subliminal dimensions are notorious for letting emotions materialise in riddles, jealousy and guilt soon propel paranoia to threaten the promising delusion.Occasionally, the film also pokes fun at the genres it inhabits, the sequence of the hitman with his gunshots wreaking a series of noise amidst the silencer—passing through the wall then lodged in the flesh of a yelping woman to the loud vacuum to the blaring of the alarm—exposes a “devised reality” reverberating a fait accompli recrudescence. Maybe this is all a surreal flash of overhauled memories of a fading/dying woman. And like everything else, the dream ends. At its wake resurfaces a confrontation with the nightmare. The demise of everything thought out to be moves aside to entangle the ruins. Interpretation is a scant task in “Mulholland Drive,” for it is at its most sublime when we allow it to install us in its mesmerisingly chimerical visuals. The sense it imparts is not the narrative, not the metaphors, not the symbols, not the colours, I don’t believe so, although it’s a privilege to get lost in its infinite layers. It is the unresolvable conundrum in ourselves, wanting to bask in dreams forever if only we don’t belong entirely to the pursuance of the inevitable reality. If only we can always mask the misery with the makings of the mind.

4. The Straight Story (1999) ★★★★

“A brother’s a brother.”Bodies are like lawnmowers, once upon a time whirring with life and pulled by its cord of joys, always ready to cut through the weeds for tidier, (un)even ground, but ultimately rusts, breaks down, putters along the closeness of mortality. Across Midwestern plains, we keep Alvin Straight company on his lawnmower in this last leg of his existential pilgrimage, an ill-stricken ride to his estranged brother who suffered a stroke. Throughout rainy days and bonfire nights, amidst a bicycle race, on snaking unpaved roads and sharp slopes, dangerous inclines and seemingly unending thoroughfares, he persists towards a familial reconciliation, aided by the kindness, presence, and stories of strangers, and his daughter with a stutter, furnishing every encounter with beats of personal recollections, these glimpses of a rough past, the innumerable ways people learn to cope. There is a serene urgency in this journey. The stubborn will to reach the destination against the hues of recurring sunsets along the flat and waving landscapes, against a supper near a parish amongst the sepulchral dead. It’s as if everywhere there’s a muted reminder of the inevitable end of one’s existence. A bittersweet familiarity of the unknown and uncontrollable. It takes its time too as it relishes the sceneries and occasional pleasures (of a bottle of beer, the smoking of tobaccos, the roasting of meat) yet also fears the possible debacle in this undertaking, the possible refusal in the anticipated reunion. As Alvin nears the home of the only brother he has, childhood makes a knot of their loose but non-severable blood ties, wooden sticks they are, previously separated by distance and dispute, again bundled together in the few words exchanged. Fraternal affection treads upon the rickety porch, where memories shared reminds of the part of himself only fully ever known to a sibling. They are this house as well, worn yet still stands, old but has braved many weathers, still a home to each other. Silence of contentment befalls them as eyes well up with tears of gratitude, of happiness. The blanket of stars over their heads looks the same as when they were young. In the near future, they’ll join their twinkling in the nebulae of their togetherness with the stardust they’re made of. It is short, this life, but it expands in moments when people allow themselves to love, to forgive; when they return to it with a softened look amongst the pile of unrecoverable, depleted years.

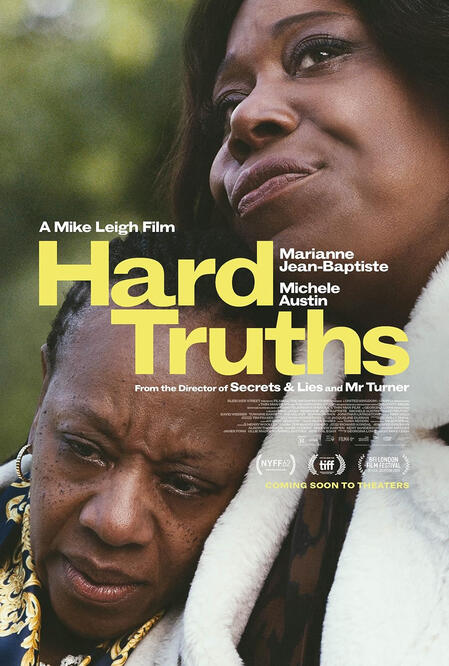

5. Hard Truths (2024) ★★★★

Bitterness accrues with the passage of time when people are stranded in endless days of unprocessed grief. In the company of unspoken sadness, the room of isolation is a damaging refuge against everything that has carried on. For the irascible and bellicose Pansy Deacon, wife of Curtley and mother of Moses, shutting herself in there is a need. She keeps it spic-and-span to conceal and contest life’s messes. She closes every door and window to shut out the noise other than the sound of her voice. Each time she is wakened, there is panic in facing a hard reality she wants to hibernate from. Each time she tries to step out, there is only anger upon her heels, upon her lips. An instinctual response to prevent revealing the depth of her suffering. Lashing out is far easier than asking for help, because asking demands vulnerability, it admits there’s something wrong. So roll the rants over the dining table, these lambastings of strangers up in the air, scoldings of those near her, and complaints everywhere. Such subconscious deflections in avoidance of self-introspection. Spilling over the rest of her family, the reclusive son she rebukes and reprimands is a mirror of herself, stuck in life, aimless like his walks, clutching a plane model and a book about planes, far-fetched dreams of getting away. Her husband, meanwhile, is quiet in his worry, yet he responds to her resentment with his own resentment, as alone as her in a family that should’ve been leaning on each other. Her sister Chantelle, again and again, reaches out to her, culminating this heartrending slice-of-Black-life at a visit to their mother’s grave on Mother’s Day, where their teary conversation is an excerpt of the unreconciled past, a spectre haunting, an animal hounding the frightened present. Flowers laid on the tomb, then later on, the kitchen counter, are a symbol of remembering the dead as much as the deadened living. A nod to the flourishes and witherings of motherhood itself. Throughout, post-pandemic malaise hovers, intimating the struggle of having to continue immediately after being coerced to pause, to experience and look at the tragedy; even taking the stairs instead of the lift is a figurative grapple with having to keep up with everything else.In careful subtlety, Mike Leigh renders a kind of generational trauma in “Hard Truths.” But where the film is profoundly perceptive is in the complexities it lends to its people while assembling the frames of a dysfunctional familial portrait. Humour is also never forgotten, dipped first in absurdity until acerbic. To talk is to be humanised here as well that the seemingly most perfect relationship never is (i.e. Chantelle’s two close daughters—who are both a contrast and a resemblance of their mother and aunt Pansy—withholds truth from each other in one scene. It seems innocuous, but it could be a gradual sagging of their closeness). With all the words spoken, none truly express what is felt.Problems never go away in “Hard Truths,” they’re not given easy resolutions either, because Mike Leigh knows some of them are life-long battles. With moments of abandonment, curves of depression, the palpable silence during the drive home recognises the repudiated rift between people, the ache of seclusion in the togetherness. How people have all these love for each other without knowing how to show it or where to put it, misplacing it where it shrinks into an accusatory absence. In time, there are more steps taken out of that room, of finally sliding the door open, however small the space, to the outside world, however brief, for its coos of gentleness, for its rustles of new beginnings. To know they’ll always be there is some consolation. For now, maybe it’s enough to let out a small sigh in brace of hope, not necessarily to repair what’s broken, but in accepting not everything can be repaired.

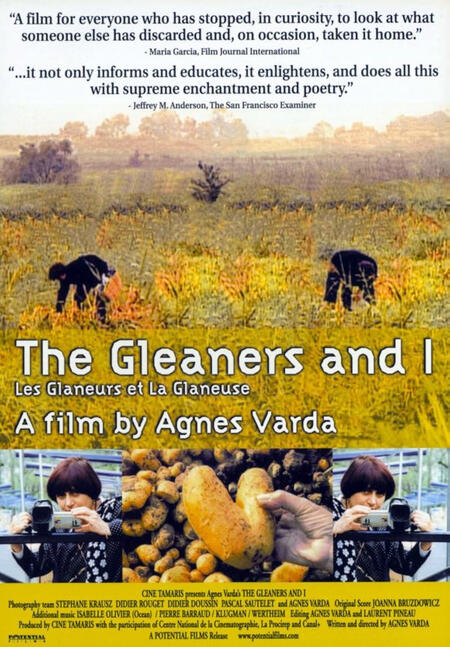

6. The Gleaners and I (2001) ★★★★1⁄2

I remember it well. It was in a supermarket where I learned of Varda's passing. Between the bread and chips aisles I stood, phone in hand, a notification from some Twitter account brought the news. I didn't finish my grocery that night. I went home with only a loaf of bread. The same brand of whole wheat I still buy six years later, then a little over a dollar now more than twice that price. There is also bread in “The Gleaners and I,” past its expiration date yet without mould, scavenged by the down and out at the back of a supermarket. It’s lying there in a dumpster amongst vegetables healthily green and fruits perfectly ripe. It’s one of Varda’s many stopovers as she takes us on a road trip, gleaning existential images upon the passing trees and trucks, along the lane markings of the highway and streets, upon the window of her vehicle, through her fingers forming a circular shape, somewhat a tunnel of time, the circle of life. On foot with her camcorder, she walks along many fields and lands. She encounters people of varying socioeconomic statuses. People who owned vineyards. People who owned fruit and oyster farms. People who owned nothing, something. Gleaning is forbidden by some due to laws. Gleaning is a season by others, a recreation for someone, a way of life, a survival for many. For a few, gleaning is a means to artistic expression. Gleaning is also fixing; it is salvaging what others deem as nothing of use. It is finding worth in the waste.From Varda’s lens unfolds a discerningly earnest documentary, touching on the history of gleaning, where the bowed down heads of gleaners are immortalised in Millet’s brushstrokes until the camera, in every frame, captures the modern gleaners in the flesh, their faces looking at her, at us. We, the gleaners. Varda, a gleaner herself. There is compassion. There is awe. There is curiosity. The film also mulls over on the kind of society we’ve built / are building, within it the ones set aside and left behind, the ones in the margins, those moving against the system, brave they are in following their passions, of having a purpose and doing something of value, these rare pickings of humanity. While “The Gleaners and I” sharply critiques (and scathingly raps about) a consumerist society manic for overproduction and overaccumulation, and the immediate disposal that follows after the fad, the trend, and the shelf life are over, it is also an affecting contemplation on this existence of ours. Like the handless clock Varda finds and places on her table top, somehow we seem to desperately wish not to have those hands. Time is seemingly in abundance in front of a dismissive eye and a careless hold, consumed without limit in the loafing hours, in the hours of meaningless labour. But there certainly arrives a moment of asking where it all went. All those hours. All those years. Some parts of you and me. Of the wasted opportunities, wasted potential, this wasted body that’ll eventually be thrown away down the bin of death, have we gleaned anything in living? Have we found anything of worth in all we wasted?

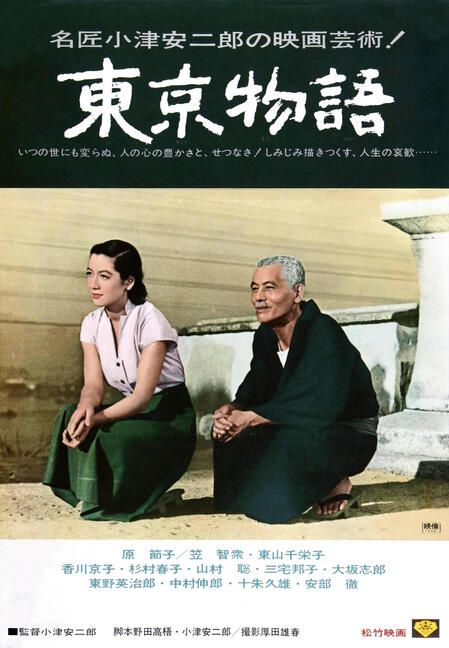

7. Tokyo Story (1953) ★★★★★

Letterboxd tells me I first saw “Tokyo Story” in 2016 when I was 23. Only a year into my romance with cinema, and only over a year into my being part of the workforce. Back then the days were long. I was impressionable. I believed if I followed a specific path, if I did a specific thing, the future will turn out how I wanted it to be. Nearly ten years later, I’m all sorts of jaded, many parts of me sceptic. I’ve learned to accept it doesn’t really turn out any way we want it to be. At least for most of us. We either end up somewhere we never thought we’d see ourselves in, or we envision a somewhere, arrive there, only for it to be something else entirely. It’s similar to the Tokyo of Ozu’s “Tokyo Story.” At times too spacious of a place without a space for its people. Other times too peopled of a place to connect its people. Or too foreign of a place for its people to remain themselves.When one of the parents remarked “Isn’t Tokyo big?” as they survey the city from a bridge, we, too, see all the urban expanse. Their words hint an urban irony of not belonging anywhere when every nook and cranny is very populated, because in this particular day they have nowhere to go, and we get the impression that they’re intruding, disturbing the routine of their children’s households in the days before. We see how their daughter and son are too occupied with their professions (one a hair salon owner; the other a doctor), too caught up with their own lives. So they send their parents either to some spa town, where the anticipated relaxation ends with the stress of a sleepless night over boisterous spa-goers, or to their widowed sister-in-law, Noriko, her tiny flat wide with warmth, her tiny flat large enough with time for them. Although Noriko has a job of her own, she clears her schedule for her in-laws and accompanies them in a bus tour. Because she has no children, no spouse, with work the only one she serves, she is tacitly expected to have an interruptible routine. Because she is a woman without ties, she can be tied to another’s errand, another’s obligation on a whim. A bit of bitterness underlies these scenes as if the parents and Noriko, both without the company of the people they want to be with (Noriko, her dead husband; the parents, their busy children), find comfort with each other. Yet, simultaneously, the sight of her in-laws is a future she currently cannot see for her solitary widowed self.Like the Ozus after, “Tokyo Story” moves in the interiors of reality with the passage of time an unstoppable instrument to the changes in people, in situations, in the family as a unit not always expanding and cohesive but divisible. Lingering in empty domestic spaces long after people have crowded the scenes, full bodies barely fit the frames across a few close-ups; and some distant shots. Outside, smoke from factories, trains on sidings, intersecting blocks of steel. Outside, tall buildings, sharp inclines, long suspension bridges. The reconstruction of post-war Japan surrounds a familial restoration. They go hand-in-hand in attempting to recapture the past with vast expectations, while the present is cramped with the demands of the daily and tradition plays catch up with modernity. What unravels is a disconnect between the younger and older generation, between the parents and their children, between those at the noon of their lives and the twilight of their years. Painfully, we also begin to realise the daughter and son have started to shrink emotionally because of the workings of the world, absorbed they are, like most of us, in the drudgery of living (“Shige used to be nicer before.” “Koichi has changed too. He used to be a nice boy.” father and mother muse about their grown-up children).“Tokyo Story” is a natural progression blatant in its portrayal; the human condition encapsulated vividly in black and white. It doesn’t edify. It evinces. It doesn’t figure. It feels. And once mortality calls and delivers itself upon the doors of the sons and daughters (like how mortality greeted and stretched its arms in Woolf’s To The Lighthouse), a pause in their lives appear in the sunrise of grief, in a brief lunch of nostalgia, each sound of the gong a loud declaration of an end. But this too passes. With most of them needing to return to their cities, to their own families—after the rashness of their actions, after their thoughtless words—everything will go on like before. (They say they still need their father, yet they leave him as soon as they could.) Only Noriko stays a bit longer, until she, too, needs to leave. Back to Tokyo. Back in Tokyo. Yes, everything will go on like before.Everyone is at the mercy of time. While it may soon be over for some, it continues for others. Noriko holds hers, a gift she will hopefully keep and use carefully, sensibly. Time is upon her. It is also upon us—to start over, to veer its course, to squander and spurn it; to do what it does best: this slipping by. So look at it. What has it done to us? Am I holding time too? Carefully? Sensibly? I guess I’m trying, all this time, but for once it embraced me, because it made me love “Tokyo Story” better.

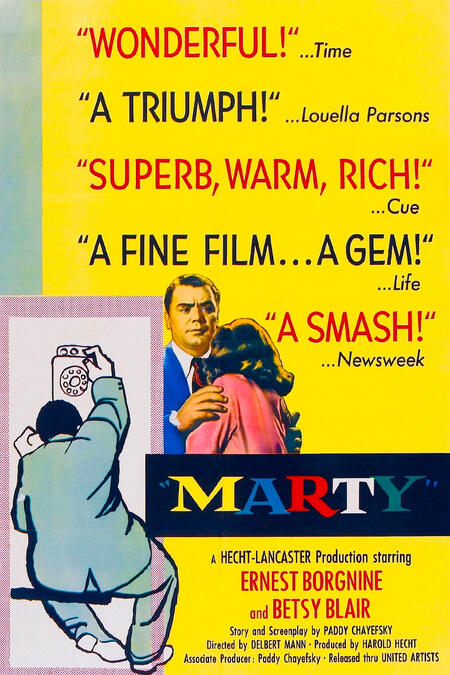

8. Marty (1955) ★★★½

Tender in the ways cruel situations coincidentally bring two lonely people together who eventually find solace in each other in a world too caught up in its revered superficialities. As everyone fixates on chasing the ephemeral standards of "eligible" attraction—the beauty that will fade, the wealth that will run out—those who do not possess them are turned away. They become outsiders, often rejected and unwanted, often partnerless in the smoky and tipsy dance halls of romance; they either sit dissolving in self-pity or roam the night for paid caresses. Ageing in their unchosen singlehood, families and friends look on with worry; the married and taken look on with judgment. Without men, unmarried (and widowed) women fade into invisibility as they try to cling to any semblance of domestic role they're shoved into. Without women, men uphold their masculinity with other men, adhering to an unspoken code to stay in the vice-filled bachelor circle. A gradual slaughter of the self with the cleaver of hatred and desperation, the debilitating silence of insecurities. For Marty and Clara, who seem to have come to terms in the belief that they’re undeserving of love, it happens in the unlikeliest of circumstances—in the slow dance of shared sorrows, in their cheek-to-cheek kindness, along the bustling evening streets of getting-to-knows, and in laughters served with a budding fondness for each other in a diner. Bliss isn't guaranteed from hereon out, however. Societal pressures continue to push them to content themselves of where and what they have, and in fear of disappointing others, in fear of change, there’s conflict between allowing themselves of happiness and remaining in the harmful comforts of loneliness. Thus, once they decide to put themselves first, embracing the possibility to want is an act of courage. It is a phone call away to ring exhausted hearts with the voice of choosing something better out of life against the what-ifs and the what-elses, to finally reach these wires of longing, a spark of self-worth, then dare themselves to love and be loved in return.

9. A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) ★★★½

I may have committed a cinephile sin in seeing the atrocious 2010 remake ten years ago (when I was in my Rooney Mara phase) before getting around Wes Craven’s OG cult classic. Last 31st October, I repented and finally let myself into the dream, immediately absolved once I let myself be devoured by its slashing synths of gore, its display of horrors so generous it never runs out of ideas to horrify and amuse. It simply knows how to have fun, while the terrorisation of a group of teenage friends—whose sleep is slowly intruded by the spirit of the child killer, Freddy Kreuger—happens underway. At first it’s a creepy chase, his finger knives stroking the pipes of scare, his whispery voice a head-messing spook, and his freshly seared meaty visage a constant nightly guest, until his attacks escalate, slicing and stabbing and slitting across a supposed restful slumber. Green blood and wormed flesh. Talons in the bathtub. A telephone tongue. One by one, the teens fall into a red eternal sleep. From the blood-soaked sheets where a clawed body spurts with the gush of death after crawling along the walls and ceiling, the carefully tied and twisted noose blanket across a sleeping neck to the sinkhole mattress that consumes and coughs up into a fountain of entrails-mixed crimson, Tina is eventually the only one left. She tries to trick and trap Freddy, arming herself with induced insomnia. But to crush fear, one has to face it. She soon surrenders to bed, her devised plan misses here and there as she and Freddy face off in the household of nightmare. It is teenage trauma encapsulated. It is the sins of the parents haunting these teens. They’re left to fend for themselves and fashion their way out of the misty basements and macabre bedrooms of these experiences. No one remains unscathed as usual. We all ride this vehicle of adolescence onto the next stage of our lives.

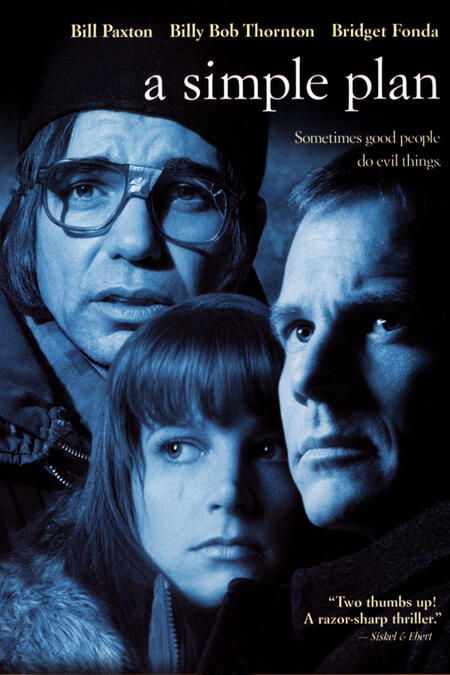

10. A Simple Plan (1998) ★★★★

The plan is supposed to be simple; spotless white as the snow-mantled nature preserve during the winter. But even the frosty surface of an ivory scheme conceals a blood-soaked melt of complications.When three men stumble upon 4 million bucks at a plane crash, their ordinary lives are suddenly perched at the precipice of an extraordinary change. But there is often a hefty price to pay in selling one’s conscience. Principles become discounted when the demand for integrity diminishes. Morals quickly go on sale. And once the avalanche of avarice skids down, covering the heads of the trio, the dynamics of dependency slips into dominoes of dissension. Slowly, turning to each other drifts into turning against each other. A bag of money for bags of bodies. Each selfish step taken worsens the consequences. Mendacity and manipulation flurry upon their caps, boots, and jackets. One is a chicken and the other is a fox and the third is a dog. The food chain of consuming greed. The ouroboros of self-ruin.A sleet of artifice. A slush of paranoia. Flakes of guilt. Frosted rectitude. The bone-chilling facet in “The Simple Plan” is not the series of desperate killings and defective cover-ups almost ridiculous in their arrival. It is not the almost hammy dramatics sinister in their underlying curve of coldness. It is these people’s very tight grip on the glimpse of a thousand possibilities when lasting financial security is at the tip of their fingertips and gun barrels. They deem themselves free at the thought of freedom inexhaustible monies bring, only to slot themselves into the very prison of its incessant temptations to possess it. But there is something else goading the acts of brutality here—the love they have for women, whether it is a fulfilment (Hank), an idea (Jacob), or somehow a revival (Lou). The impetus necessary to garb oneself with the thick layers of self-interest that everyone else becomes a bothersome speck across the illusory landscape of affluence. There is also Hank’s wife who we can consider as the mastermind so far as we speak of causes and effects that set the big chunk of the story in motion. It underscores the ironic fear of loss that incessantly piles up throughout. Once it engulfs the entirety of the film—after people are slain as sacrificial lambs for the altar of the money god (perhaps, with some allusion to Cain and Abel)—even the immensely coveted reward made of prized paper is turned into an offering, burnt into mere cinders of cheaply made wood pulp. Everything becomes meaningless. Everything becomes the same. All is for nothing when the value of one’s humanity is a debt of dreams, the dues of desire.

All movie posters are from IMDB | letterboxd.com/spacelessvoid